The New York Times Magazine’s story “Who is the Bad Art Friend?” sparked a flurry of online debate about friendship, literary ethics, and social media use. Much of the discourse revolved around the personal dispute between the two main characters, Dawn Dorland and Sonya Larson, but copyright law also played a role in the story: the case ended up in court, in part, because Dorland alleged copyright infringement against Larson’s story, “The Kindest.” The drama raises questions about copyright’s competency to deal with literature that draws heavily from authors’ lives, like confessional literature or autofiction. And given how copyright doctrine has treated other forms of contemporary art, the outlook for its treatment of those literary styles is not encouraging.

The New York Times Magazine’s story largely lays out the facts of Larson v. Perry. In June 2015, Dawn Dorland Perry (who goes by Dorland) donated her kidney through a “nondirected donation,” meaning that she did not donate her kidney to a specific person — instead, it went to whomever needed it through a “donation chain.” Dorland then made a Facebook group to keep a group of friends updated on her experience. The posts in the group included a letter that Dorland had written to the ultimate recipient of the donation chain that she had started. Shortly thereafter, Sonya Larson, who was in the Facebook group, began writing a short story about a nondirected kidney donation titled “The Kindest.” Dorland reached out to Larson about the story, and Larson maintained that the story was not about Dorland but merely inspired by her donation. However, when Dorland read the story, she felt that the story was, in fact, heavily based on her donation. Dorland was further incensed that Rose, Larson’s donor character, wrote a letter that was heavily reminiscent of, and in some versions matched almost verbatim, the letter that Dorland had written to the recipient of her kidney. Dorland then began to contact groups that had published or recognized “The Kindest,” alleging that the story included plagiarized material. One of these publishers, Boston Book Festival’s “One City One Story,” cancelled its event for that year, citing the risk of litigation in light of Dorland’s claims.

After receiving demand letters from Dorland’s legal counsel, Larson sued Dorland and her legal counsel in the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts seeking a declaratory judgment that “The Kindest” did not infringe Dorland’s copyright of the letter. Larson also alleged tortious interference and defamation arising out of Dorland’s accusations of plagiarism. Dorland brought counterclaims alleging copyright infringement of her letter, as well as intentional infliction of emotional distress. Larson moved for the Court to dismiss both of Dorland’s claims for failure to state a claim.

The court dismissed Dorland’s emotional distress claim, but not her copyright claim. For the copyright claim, Larson had argued that Dorland had not pleaded actual infringement and that even if Larson had infringed Dorland’s copyright, that infringement was a fair use because she had “transformed” Dorland’s letter by imbuing it with a new meaning. The court rejected both defenses on the grounds that they were too fact-intensive to assess at the motion to dismiss stage. The court also declined to dismiss Dorland’s copyright claim on the grounds that she had been only nominally damaged, noting that she would be entitled to declaratory and injunctive relief if she won. As for the emotional distress claim, the court found that Larson’s conduct was not “extreme and outrageous” as a matter of law and accordingly dismissed the claim. The case has since moved into discovery.

The court’s decision in Larson highlights a tension between copyright doctrine and contemporary art. The bar to receive copyright protection is low, with courts recognizing infringement for increasingly small works. Because infringement is easy to assert as a prima facie matter, courts often rely on doctrines like “fair use” to ensure that copyright protection does not “stifle the very creativity which [copyright] law is designed to foster.” The fair use doctrine permits the unlicensed use of copyrighted material without constituting infringement under certain circumstances. As part of the fair use analysis, courts will often ask if a work is “transformative”: that is, whether it “alter[s] the first with new expression, meaning, or message.” The transformative use question tends to be dispositive: when a court finds that a use is transformative, it is much more likely to find that a use is fair than otherwise.

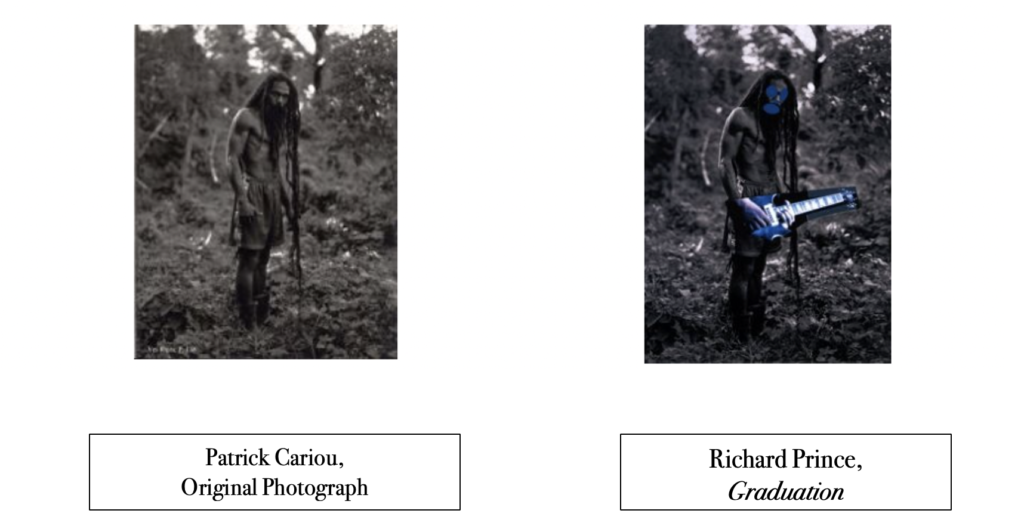

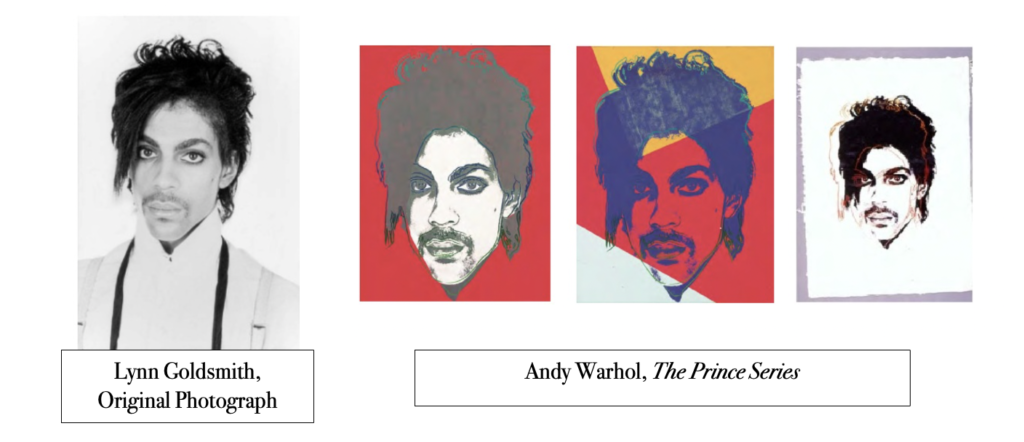

Contemporary art, especially appropriation art, has caused particular problems for transformative use doctrine. Appropriation art is art (which is often, but not always, visual art) that uses pre-existing, and sometimes-copyrighted material as part of its artistic expression, often without significant alteration. That appropriation art often purposefully uses copyrighted material combined with transformative use’s fact-specific nature makes it difficult to predict whether any given use will be transformative. For this reason, commentators have argued that the doctrine “does not provide a coherent body of law”. Others have questioned whether the transformative test is appropriate for contemporary art at all, given that it compels courts to “search for ‘meaning’ and ‘message’ when one goal of so much current art is to throw the idea of stable meaning into play.” The “high-water mark” of transformative use is Cariou v. Prince, which found that most of the uses of copyrighted work in a series by appropriation artist Richard Prince were transformative even though the copyrighted work was often clearly recognizable in the allegedly infringing work. The Cariou decision has been controversial — even the Second Circuit, which decided Cariou, has noted that it “has not been immune from criticism.” The Second Circuit also recently distinguished the works in Cariou from a series of Andy Warhol works in a case that made clear that Cariou did not establish a bright-line rule.

The Second Circuit found Prince’s work to be transformative in Cariou v. Prince (above), but did not find Warhol’s works, which incidentally involved the musical artist Prince, to be transformative in The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith (below).

Although the tension between copyright protection and contemporary art is stark in the appropriation art context, Larson demonstrates that that tension can spill into other areas of art, including literature. The current trend in the fair use doctrine could pose particular problems for increasingly popular genres like autofiction, which is an example of highly personal literature that intentionally blurs the line between fiction and an author’s real life. For example, in Book One of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s controversial autofiction My Struggle, the author includes excerpts from letter correspondence between himself and another author, Kjarten Fløgstad. To be sure, Knausgaard’s use of Fløgstad’s letters is not as extensive as Larson’s use of Dorland’s (at least in some versions of “The Kindest”). Nevertheless, following Larson, Fløgstad could reasonably bring a copyright claim against Knausgaard that could survive a motion to dismiss and go to discovery. Of course, “The Kindest”was not an autofiction, but the argument against transformativeness might even be stronger for an autofiction than it was in Larson. If importing a letter into a fictional short story is not giving that letter a new “expression, meaning, or message,” it seems unlikely that Knausgaard’s use of Fløgstad’s letters, which keeps those letters in the same context in which they appeared in real life, is any more transformative.

The mere fact that Larson went to discovery, although consistent with the current trend in copyright law, is no trivial matter. The muddy and fact-specific nature of the transformative use analysis means that trial courts are reluctant to assess whether a work is transformative before discovery, as happened in Larson. Accordingly, infringement cases that revolve around transformative use often go to discovery, which, as Larson demonstrates, can be extensive. However, it is not even clear what discovery could reveal about the transformativeness inquiry in a case like Larson. Even if discovered documents show, as some have argued, that Larson wrote the story as a “takedown” of Dorland, the story would still provide Dorland’s letter with a new “expression, meaning, or message” — Dorland presumably did not write the letter to be a “takedown” of herself. Thus, discovery might not bear much on the transformativeness analysis, but it does impose costs on authors. Litigants pay higher legal fees as the case goes on, which itself disincentivizes artists from drawing from their own lives in this way — and the publicity of “Who is the Bad Art Friend?” demonstrates the unwanted attention that litigation can bring. Authors therefore might be apprehensive about using written material from their own lives if there is a looming threat of litigation and discovery, even if that litigation would ultimately be unsuccessful. For authors of autofiction, copyright law may come dangerously close to stifling the creativity that it is meant to promote.